Can LLMs give us AGI if they are bad at arithmetic?

This text of this post was written without AI assistance or editing.

Wes does vibe coding

Up until about March of this year, I regarded AI-assisted development with skepticism, avoiding LLM-powered autocomplete or “AI IDEs” like Cursor and Windsurf. Most of my career’s work from 2008 onward was done in emacs without even the assistance of LSP. In retrospect, a modest investment in developer tooling (e.g. LSP-integration and tab complete in emacs) would probably have made development a little more enjoyable, but its absence didn’t prevent me from getting things done.

The first thing that got excited about LLM-assisted development was Anthropic’s Claude Code (CC). Almost overnight, I discovered that I could now delegate a large amount of low-value “drudgery” work (especially on CI/CD tooling, sysadmin, and routine codebase cleaning / refactoring) that I used to have to suffer through for the greater good. More than 8 months in, it has already been a huge productivity boon when given the right kind of tasks. Discovering its limitations and cognitive deficits has required a lot of trial and error, though never failing to be interesting or engaging to use.

One of my favorite ways to use CC is in the creation of “bespoke tools”, the kinds of low-complexity projects you used to think about building but never actually built because you couldn’t justify the time investment. I think of these like “bad projects for interns”. Now there is nothing getting in your way if you’re willing to give CC (or your preferred coding agent) a bit of code review, design feedback, and human-in-the-loop QA testing. For example, I recently used CC to make the personal bookkeeping tool (moneyflow) I always wanted from scratch.

While I’ve been having fun building stuff with Claude Code, the frequent joy and satisfaction are met frequently by bouts of frustration and suspicion that remind you that you are working with a non-deterministic model that fundamentally lacks self-awareness. Some of the first things that come to mind include:

- Repeatedly ignoring or “forgetting” the instructions in

CLAUDE.mdabout fixing code style issues or checking Python types before committing. - Completely fabricating benchmark result data when it couldn’t get something working and representing these benchmark results as the output of a benchmarking script.

- Navigating the development workflow in a complex project consistently and competently one week and then not at all the following week (with the same model and same set of prompts).

Overall, it’s been hard for me to see the current iteration of coding agents as being more than a mostly effective way for experienced developers to accelerate routine software development tasks or fill in routine knowledge or skill gaps, a far cry from being the early stages of emergent superintelligence.

Hyperbole and reality

What I often tell people about coding agents like Claude Code is that they provide the most leverage to people who can articulate well what they need from the agent and have the aptitude to review and give feedback on the generated output like a senior engineer might do with a junior engineer or intern. From what I’ve seen, without a foundation of software engineering experience and a knack for technical communication, a user of one of these agents on any non-trivial project will rapidly drown in the sea of slop they produce and become unable to progress. But that’s actually not what this blog post is about.

I have been having difficulty lately reconciling the feeling of LLMs, including the coding agents, having glaring cognitive deficits (even if those deficits have improved substantially with the latest frontier models, e.g. Sonnet/Opus 4.5) with the prevailing sentiment that “AGI is just around the corner”. Some have predicted that it’s only a year or two away while OpenAI’s Sam Altman has stated “certainly by the end of the decade”.

I am not an AI researcher, but I wanted to highlight a cognitive deficit that I encountered on an LLM-powered repo activity summarizer that I built during an AI hackathon. I found that the frontier models surprisingly struggled to do basic arithmetic, such as computing simple sums from small tables of numbers.

I was reminded of this problem last week when reading Anthropic’s recent blog on a new Advanced Tool Use feature. In it, they describe a reasoning problem where the LLM would make a bunch of tool calls and then “manually sum” a 2000-line table of tool call results:

Traditional approach:

- Fetch team members → 20 people

- For each person, fetch their Q3 expenses → 20 tool calls, each returning 50-100 line items (flights, hotels, meals, receipts)

- Fetch budget limits by employee level

- All of this enters Claude’s context: 2,000+ expense line items (50 KB+)

- Claude manually sums each person’s expenses, looks up their budget, compares expenses against budget limits

- More round-trips to the model, significant context consumption

I actually laughed out loud when I read this. Not only would I not be confident about 2000-line table passing intact through the context window, but I have seen the models struggle to sum up even small lists of numbers (tens, not hundreds or thousands). Maybe when they wrote “manually sum” they really meant “call another tool” or “generate Python code to do the math”, but even so passing a non-trivial amount of data through an LLM context is computationally wasteful and may result in data loss (the question of how LLMs should handle tabular data could be another blog post entirely).

So how bad are LLMs at arithmetic?

My reaction to the Anthropic blog post was based only on my anecdotal experience, so I decided to make some GPUs go brrrrr and find out where the arithmetic skill breakdown takes place.

Here is the problem formulation: given a small CSV transaction dataset with group ids and integer values from 0 to 10, compute the sum of values by group. Here is an example prompt to be sent to the LLM:

# System Prompt

You are a data analyst. When given CSV data, analyze it and provide the requested aggregation.

Return ONLY the result in CSV format with no additional text or explanation.

Do not use any tools or code execution - compute the answer directly.

# Prompt

Here is a CSV data table:

txnid,groupid,value

1,g3,6

2,g2,5

3,g1,4

4,g1,2

5,g2,3

6,g3,5

7,g1,1

8,g2,1

9,g1,6

10,g3,1

Please compute the sum of 'value' grouped by 'groupid' and return the result as CSV.

Return ONLY the CSV output in this exact format, with no other text:

groupid,sum_value

<group1>,<sum1>

<group2>,<sum2>

...

Expected answer: g1: 13, g2: 9, g3: 12I wanted to see how accurate the results were for different models (OpenAI, Anthropic, and local models running on an NVIDIA GPU – a DGX Spark actually – at home), numbers of rows, and numbers of groups. For example, I would expect the models to be more accurate on a 10-row table with one group than a 100-row table with ten groups.

I had previously read a blog post about LLMs’ ability to do retrieval (looking up values based on a query) on tabular data formatted in different ways, so I was curious to see how things performed on a wider variety of models (beyond the gpt-4.1-nano used in that blog post) and on a problem less trivial than looking up values in a table.

Results

These result tables reflect accuracy out of 100 trials for each case. When there are multiple groups, the number of values per group is about the same, and for the larger number of groups I omit the cases where the number of rows is the same or smaller than the number of groups (since there is no addition happening). I organized them by the number of groups in the input dataset, and in the columns are the number of rows. As for the models, the ones tested were:

- OpenAI: GPT-4o, GPT-4o-mini, GPT-4.1, GPT-4.1, GPT-4.1-nano (no GPT-5, I will explain why below!)

- Anthropic: Haiku-3.5, Sonnet-3.7, Sonnet-4, Haiku-4.5, Sonnet-4.5, Opus-4.5

- Local: GPT-OSS-20b, GPT-OSS-120B, Qwen2.5-Coder

1 Group

In the single group case, the model must simply add up all the values in table rather than computing totals by group. What’s interesting here is that all of the API models start to fail at some point beyond adding up 10 values. The local GPT-OSS models running on my DGX Spark perform great, but the Qwen local model shows similar behavior (but overall worse performance) to the small, cheap API models.

| Model | 10 rows | 50 rows | 100 rows |

|---|---|---|---|

| Claude 3.5 Haiku | 70% | 1% | 0% |

| Claude 3.7 Sonnet | 100% | 0% | 0% |

| Claude Haiku 4.5 | 100% | 1% | 0% |

| Claude Opus 4.5 | 100% | 2% | 0% |

| Claude Sonnet 4 | 100% | 2% | 1% |

| Claude Sonnet 4.5 | 100% | 3% | 2% |

| GPT-4.1 | 100% | 4% | 2% |

| GPT-4.1 Mini | 100% | 5% | 0% |

| GPT-4.1 Nano | 57% | 4% | 0% |

| GPT-4o | 100% | 0% | 1% |

| GPT-4o Mini | 54% | 2% | 0% |

| GPT-OSS-120B | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| GPT-OSS-20B | 100% | 100% | 99% |

| Qwen2.5-Coder-32B | 37% | 1% | 0% |

10 Groups

In the 10 group case, we see some of the API models perform a little better, presumably since there are only ten values to add per group in the 100 row case. All of the OpenAI API models fail at 100 rows, while the Anthropic models are a mixed bag, with the recently released Opus 4.5 doing the best. Still the local GPT-OSS models perform the best overall and in general even better than the frontier models.

| Model | 10 rows | 50 rows | 100 rows |

|---|---|---|---|

| Claude 3.5 Haiku | - | 19% | 0% |

| Claude 3.7 Sonnet | - | 100% | 38% |

| Claude Haiku 4.5 | - | 11% | 0% |

| Claude Opus 4.5 | - | 100% | 95% |

| Claude Sonnet 4 | - | 97% | 14% |

| Claude Sonnet 4.5 | - | 97% | 23% |

| GPT-4.1 | - | 58% | 0% |

| GPT-4.1 Mini | - | 14% | 0% |

| GPT-4.1 Nano | - | 0% | 0% |

| GPT-4o | - | 90% | 3% |

| GPT-4o Mini | - | 1% | 0% |

| GPT-OSS-120B | - | 100% | 99% |

| GPT-OSS-20B | - | 100% | 89% |

| Qwen2.5-Coder-32B | - | 0% | 0% |

25 Groups

With 25 groups, there are only 2 or 4 values per group depending on the case, and so we see better performance across the board:

| Model | 10 rows | 50 rows | 100 rows |

|---|---|---|---|

| Claude 3.5 Haiku | - | 95% | 3% |

| Claude 3.7 Sonnet | - | 100% | 98% |

| Claude Haiku 4.5 | - | 98% | 2% |

| Claude Opus 4.5 | - | 100% | 100% |

| Claude Sonnet 4 | - | 100% | 95% |

| Claude Sonnet 4.5 | - | 100% | 95% |

| GPT-4.1 | - | 100% | 24% |

| GPT-4.1 Mini | - | 95% | 0% |

| GPT-4.1 Nano | - | 1% | 0% |

| GPT-4o | - | 100% | 72% |

| GPT-4o Mini | - | 1% | 0% |

| GPT-OSS-120B | - | 100% | 100% |

| GPT-OSS-20B | - | 98% | 94% |

| Qwen2.5-Coder-32B | - | 41% | 0% |

Studying the dropoff

It’s interesting that most of the API models, even the smaller models, can add up ~ten single-digit numbers pretty consistently, but somewhere after that things start to break down.

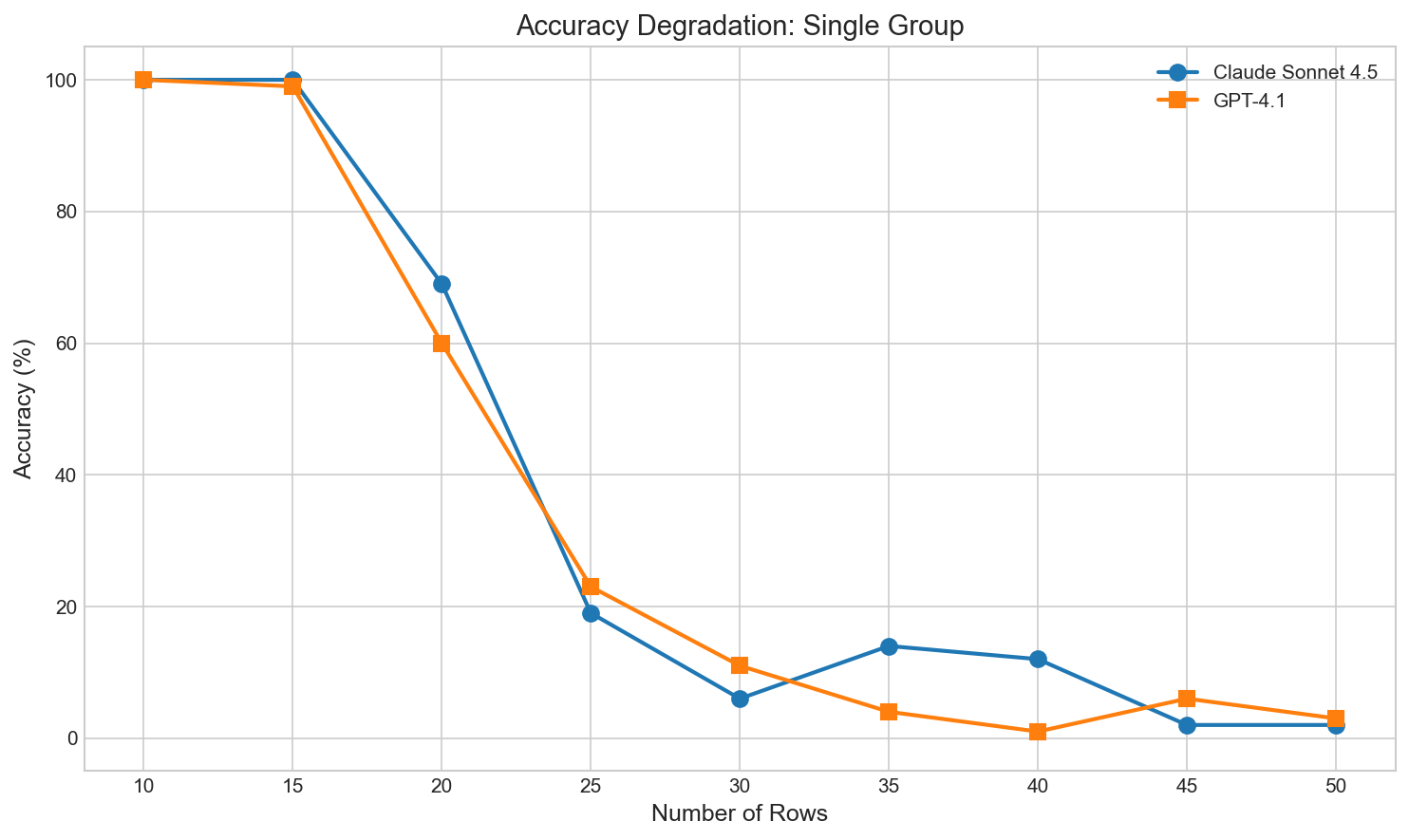

I ran 100 trials for Sonnet 4.5 and GPT-4.1 to see at what point the models start to struggle to add the numbers. It seems it’s somewhere around 20-25 single-digit numbers. I haven’t run the analysis for more complex numbers (like dollar-and-cents less than $10) but I would guess the more complex the numbers (here it’s numbers from 0 to 10) the worse the performance:

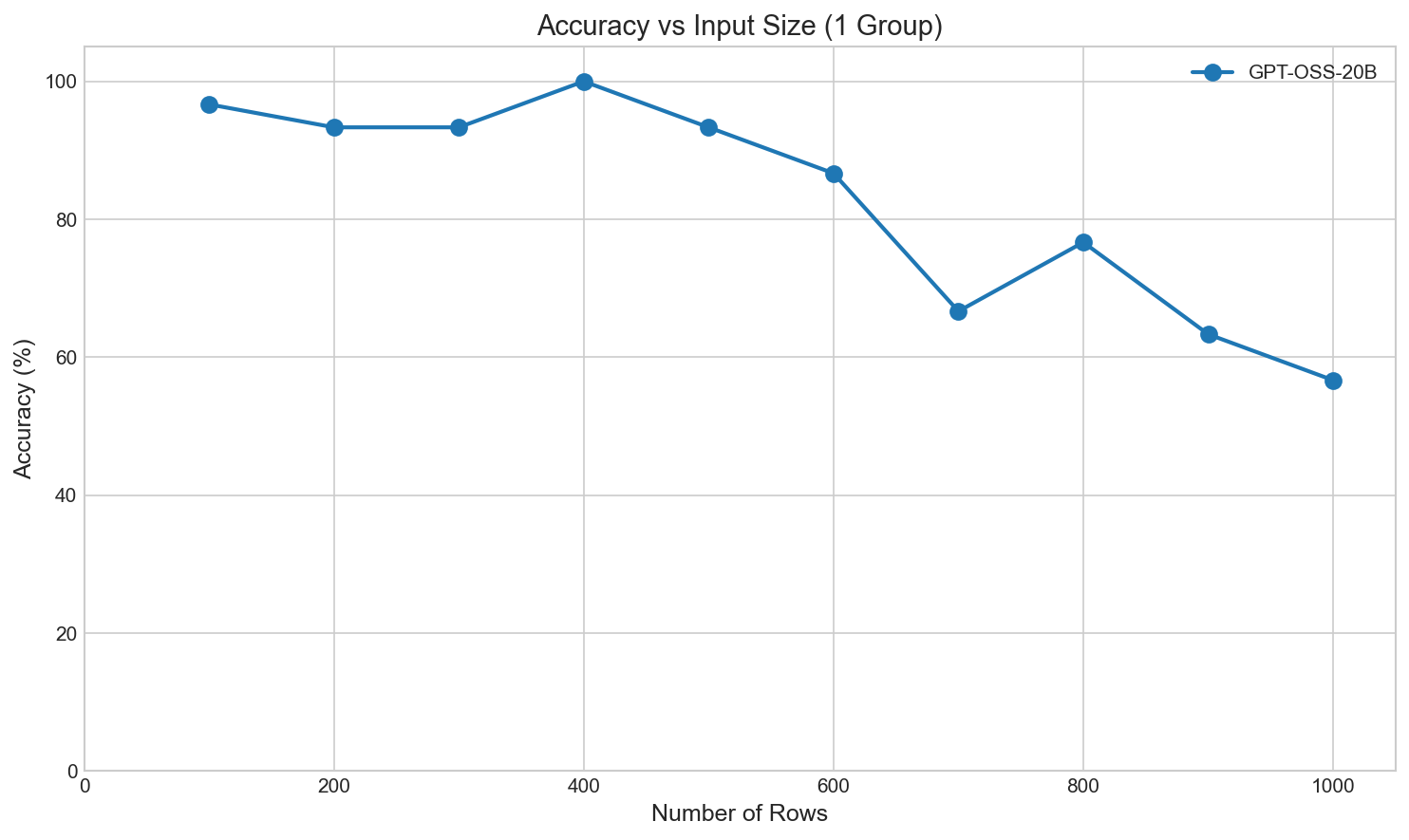

Since the local GPT-OSS models perform much better than the API models, I ran 30 trials per case across a grid out to 1000 rows of data, which shows some degradation as the dataset gets larger:

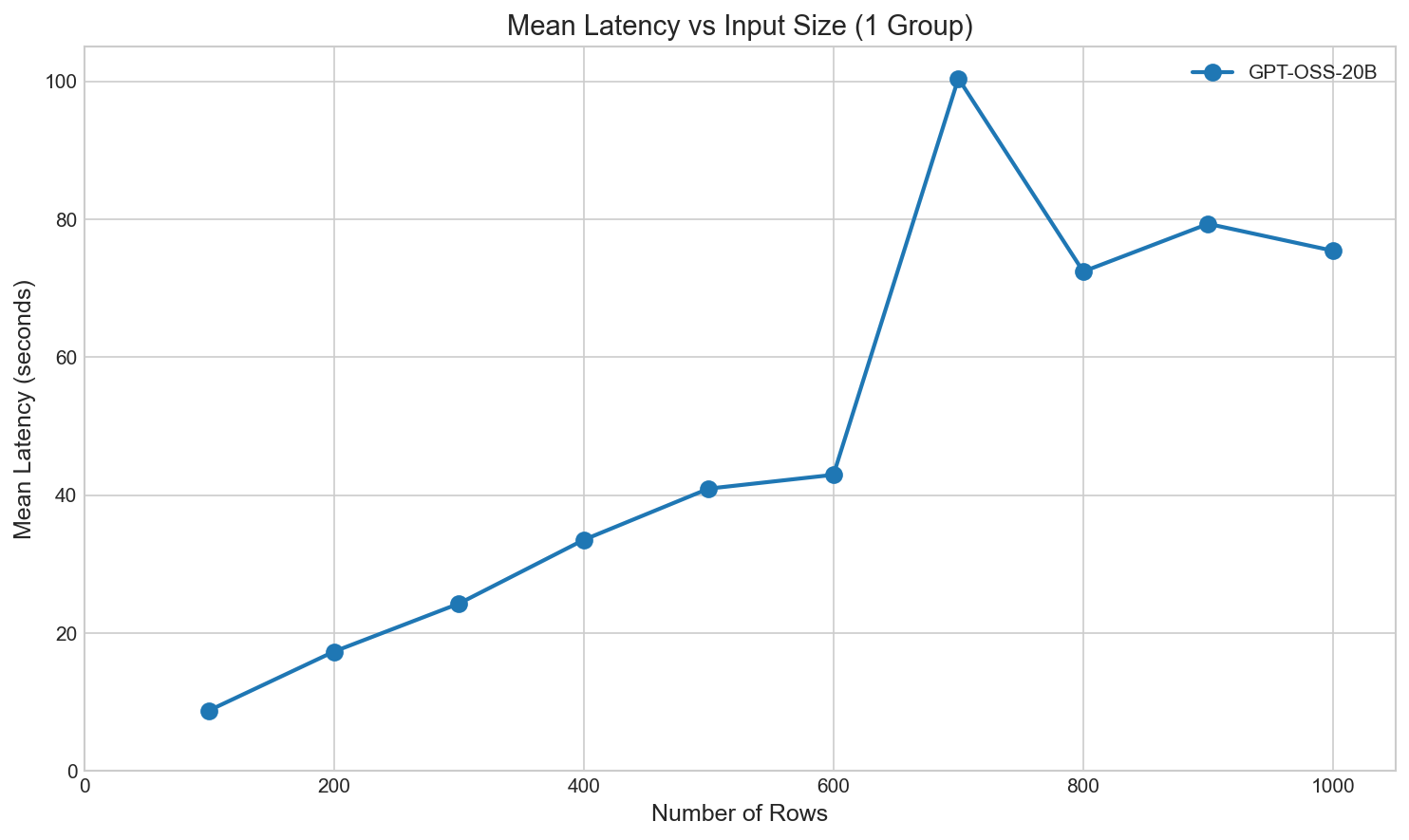

However, the inference time (here on an RTX 5090 – the DGX Spark turns out to be quite slow for inference and life is busy) leaves something to be desired:

Where is GPT-5?

I omitted GPT-5 from the study because I immediately noticed it was different from all the other API models and that running the 700 or so trials for the above tables was taking too long.

First, it returned correct answers even for a 1000-row table with one group, where the older models struggle with adding even a couple dozen values. That was suspicious. The GPT-OSS open weights models have high accuracy on small datasets, but start to degrade above 400 rows.

Secondly, the requests were taking much longer (here is the 100 row, 1 group case):

| Model | Trial 1 | Trial 2 | Trial 3 | Trial 4 | Trial 5 | Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| gpt-5 | 25.54s | 13.92s | 39.68s | 15.09s | 46.66s | 28.18s |

| gpt-4.1 | 0.57s | 0.60s | 0.53s | 1.23s | 1.17s | 0.82s |

gpt-5 is 34.3x slower than gpt-4.1 on this task.

I had read about GPT-5 when it was announced and specifically its “router” that decides how to handle your request:

GPT‑5 is a unified system with a smart, efficient model that answers most questions, a deeper reasoning model (GPT‑5 thinking) for harder problems, and a real‑time router that quickly decides which to use based on conversation type, complexity, tool needs, and your explicit intent (for example, if you say “think hard about this” in the prompt).

So I guess either the “deeper reasoning model” is kicking in to (very slowly) add up 100 single-digit numbers, or GPT-5 is calling tools (again, very slowly) behind the scenes. Given how dreadfully slow it is, I’m more inclined to think it’s due to “heavy inference” vs. “slow tool calling”. If anyone knows more about what’s going on I’d be interested to know.

Model overconfidence and Tools

An obvious reaction to these results is “Wes, the models aren’t being trained to solve this problem, that’s what tool calling is for.” I agree.

But the models themselves aren’t even “aware” of their incompetence, which is troubling. I asked Claude Code to create a prompt for the models to give an honest estimate of their accuracy percentage, here are the results:

Task: Sum 50 values (0-10) presented as CSV (prompt)

| Model | Self-Reported Accuracy |

|---|---|

| GPT-OSS-20B | 90% |

| GPT-OSS-120B | 98% |

| Qwen2.5-Coder-32B | 95% |

| GPT-4o | 90% |

| GPT-4o Mini | 95% |

| GPT-4.1 | 98% |

| GPT-4.1 Mini | 98% |

| GPT-4.1 Nano | 85% |

| GPT-5 | 85% |

| Claude 3.5 Haiku | 100% |

| Claude 3.7 Sonnet | 95% |

| Claude Sonnet 4 | 85% |

| Claude Sonnet 4.5 | 73% |

| Claude Haiku 4.5 | 92% |

| Claude Opus 4.5 | 62% |

It is clear that these models need to offload any non-trivial data-related task to tool calling to make accurate judgments, but given this Dunning-Kruger-esque false confidence, they may opt not to (or forget to) invoke tools even if explicitly instructed to do so.

A related concern is that these models routinely make dozens of tool calls as part of generating a response to a prompt, as as we have seen above, dozens of anything is a problem. It’s fine if Claude Code is helping me write Linux sysadmin scripts for my local inference servers, but delegating business decisions to a fleet of agents that can’t count good? I’m not so sure.

Takeaways and Thoughts

LLMs, coding agents in particular, are tremendously useful tools that have already saved me huge amounts of time this year. It’s hard to imagine going back to the “old days” of doing everything by hand, and especially struggling through tedious tasks (like devops or sysadmin work) where I lack in-depth experience. Based on what I’ve seen, the more software engineering experience you have and the better your judgment and intuition, the more helpful coding agents are. However, as useful as LLMs can be, it’s hard to look at the frontier models in isolation and see something approximating human-level intelligence when there are such evident cognitive gaps.

The above analysis makes it clear that LLMs aren’t being fine-tuned to make accurate judgments about even small datasets. In fact, it seems pointless to waste input tokens on putting data in the context window. That said, there needs to be a more efficient way to attach data “sidecars” (e.g. in Arrow or Parquet format) that do not burn tokens but which allow the LLMs to pass the datasets through to efficient tools (e.g. using something like DuckDB or DataFusion to do analytics on tables). This would make the tool calling a great deal more efficient than pushing data through the LLM in CSV or JSON format, which feels like a major regression after spending the last 15 years developing efficient open standards for moving around large datasets.

The code to reproduce the analysis in this post is located on GitHub